|

Lance Thompson: What Inspired My 12-Years Old

Self This web

page replaces balmerino.info Kennedy Space Centre: January 2012 (This revision March 2025) "Soon there will be no one who remembers

when spaceflight was still a dream, the reverie of reclusive boys and the

vision of a handful of men" Wyn Wachhorst |

||||||

|

Space

Geek |

What

is it that inspired me as a child? I was born in July 1957, just before

the Space Race began, in October 1957, with the launch of Sputnik-1. And only 12-years from the first manned

space flight to land on the moon. I was very sorry to hear of the death

of Neil Armstrong (25 Aug 2012). As inevitable as such

events are, it is testament to the increasingly

distant era of mankind's greatest adventure. It has taken until now, January 2012,

for me to visit the place where it all happened. I have edited this page several times

since 2012. This current edit, March 2025, is to celebrate, finally, a return

to manned space flight beyond low Earth orbit. NASA’s SLS (Space Launch System) and

Orion spacecraft will, hopefully, return men and women to the lunar surface

by 2026 with Project Artemis. The grand old lady Saturn-5 is no

longer the most powerful flying machine; SpaceX Starship

powered, on the first stage, by 33 Raptor engines, is even more powerful.

However, there is still a record that’s likely never to be broken: The F1,

with a lifting potential of 600-Tonnes per engine, will hold the record for

the most powerful single chamber liquid-fuel rocket engine ever built and

used. (See Rocket Science at the end of this page) |

|||||

|

The

‘Rocket Garden’ |

Project

Mercury: 1958-1963 The rockets that carried the first

sixteen American manned spacecraft in to space were simply those same

machines intended to deliver nuclear warheads. The first two astronauts, Alan Shepard and Virgil Grissom, where boosted aloft by the Redstone missile in a Mercury capsule (right-hand side in this image). The

next four astronauts, John Glen, Scott Carpenter, Walter Schirra and Gordon Cooper were launched in to orbital flight atop

the Atlas missile (left-hand side in this

image). It was probably seeing the T.V.

coverage of Gordon Cooper's flight and, soon after, my being given a book on

space - Timothy's Space Book - that sparked my

interest. My early interest later developed in

to a passion for science and engineering. Interesting note: at the time of

these flights, Gerry and Sylvia Anderson were producing the children's T.V.

series Thunderbirds. Those old enough to

remember the shows will notice a striking similarity of the names of the

characters and the astronauts of Project Mercury! |

|||||

|

|

Project

Gemini: 1961-1966 After Project Mercury, which were

single astronaut missions, came Project Gemini carrying two astronauts. Their booster

was a Titan missile, seen in the centre of this image. The Gemini Astronauts: Gemini-3: Virgil Grissom & John Young Gemini-4: James McDivitt & Edward White Gemini-5: Gordon Cooper & Peter Conrad Gemini-7: Frank Borman & James Lovell Gemini-6a: Walter Schirra & Thomas Stafford Gemini-8: Neil Armstrong & David Scott Gemini-9a: Thomas Stafford & Eugene Cernan Gemini-10: John Young & Michael Collins Gemini-11: Peter Conrad & Richard Gordon Gemini-12: James Lovell & Edwin Aldrin |

|||||

|

Gemini was the test bed for all of

the techniques and skills that would be required to get to the moon. Mercury

and Gemini used launch rockets that were 'off the shelf' cold-war missiles.

Still missing were the machines that would make manned flight to the moon

possible. From 'Rockets to the Moon' being just science fiction, to the test

launch of the most powerful flying machine ever created, took less than

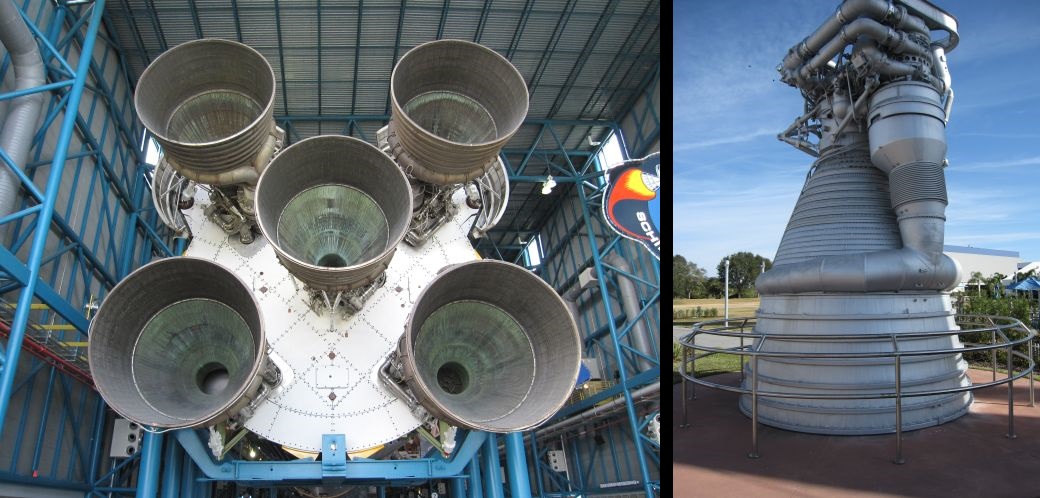

6-years. The Saturn-5 Moon Rocket Everything

about the Saturn-5 is as impressive today as it was back in the 1960's.

This image is of the cluster of five F1 liquid-fuel rocket engines, powering the first

stage of the Saturn-5. Each F1, the right-hand image, (nearly 12-feet in

diameter at the nozzle) was capable of lifting over 600-tonnes off the

ground. Each F1 consumed over 2.6-tonnes of propellant per second. Together

the five F1s could lift the all-up weight of 2800-tonnes Saturn booster, and

its Apollo spacecraft, off the launch pad and propel the vehicle for the

first 70-miles. With a notional fuel consumption of 5-inches-per-gallon, it

was not going to win any fuel-efficiency competition! At engine cut-off the

spacecraft was travelling at around 1.5-miles-per-second. The

F1 is still the most powerful single chamber liquid-fuel rocket engine ever

created. (See Rocket Science at the end of this page) At

launch, the five F1 engines together produced over 44-gigawatts of mechanical

power, equivalent to around 1-million family motorcars! An

absolutely stunning YouTube video of a Saturn-5 launch, with slow motion of

the F1s |

||||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

If, like me, you're wondering

about the music used in this video: Baltars Dream and Roslin and Adama, both

by Bear McCreary Back in 1972 I made a sound recording

(with my first cassette tape recorder) of the launch of Apollo-17. Broadcast by

the BBC on the 7th December 1972, with James Burke and Patrick Moore commentating. It was the only

night-time launch of a Saturn-5, and the emotional effect of lighting up the

sky with a forty-four-thousand-megawatt candle is very evident in the

recording. Click the video frame below to listen to the launch: |

||||||

|

|

|

|

||||

|

There

are three unused Saturn-5 boosters; they would have been Apollo 18, 19 and

20. At Kennedy

Space Centre the Apollo Saturn-5 moon rocket is displayed as separate stages

and units.

Moving

along the 363-ft length of the Saturn-5

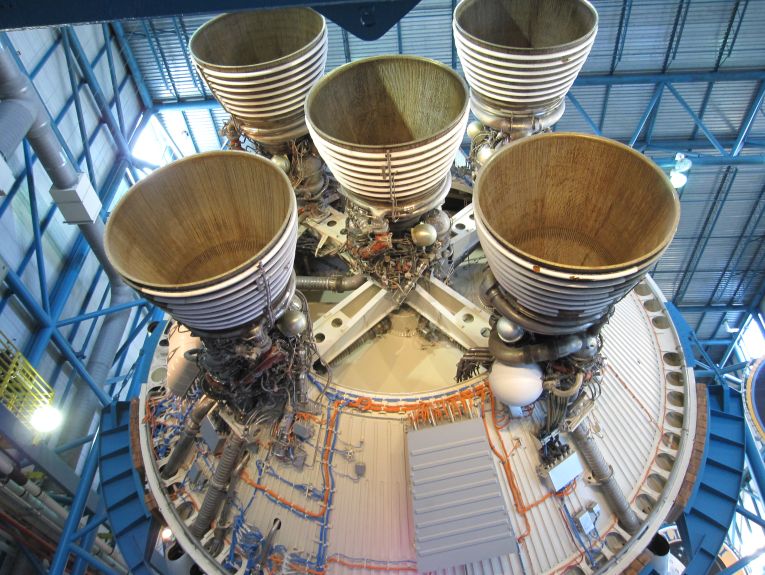

A

cluster of five J2s providing the thrust of the second stage of the Saturn-5 |

||||||

|

Whereas, perhaps, not quite as

impressive as the F1, each J2 produced over 100-tonnes of thrust. When these

engines were exhausted the spacecraft was travelling at nearly

5-miles-per-second, and was almost in Earth orbit at a height of 100-miles.

The third, and final, stage of the

Saturn-5 was powered by a single J2. This engine was fired twice: first to slip

the spacecraft into Earth orbit, and second to propel the spacecraft towards

the moon. After the third stage was finally

exhausted, the Apollo spacecraft had a velocity of 7-miles-per-second and was

moon bound. To put together the largest rocket ever

built, you need the biggest single enclosure structure ever built. At 526-ft

tall, with a volume of nearly 130-million cubic feet, the Vertical Assembly

Building (VAB) is a very large structure!

Now

renamed the Vehicle Assembly Building, the flag is 209-ft by 110-ft, giving

some scale to the colossal VAB. We

were lucky to have visited Kennedy Space Centre just as they

started visitor tours of the VAB.

Launch Complex 39A: the launch

location of Apollo-11. |

||||||

|

|

The

Apollo Missions: Apollo-7: test flight of the Apollo Command and

Service modules Apollo-8: first manned flight to leave Earth orbit

and fly to the moon Apollo-9: test flight of the Lunar Module, in Earth

orbit Apollo-10: all but land on the lunar surface flight

to the moon Apollo-11: first manned space flight to land on the

moon. Sea of Tranquillity Apollo-12: second manned landing on the moon. Ocean of Storms Apollo-13: near tragedy, perhaps the greatest rescue

story of all time Apollo-14: extending the science objectives near the

big crater Fra Mauro Apollo-15: with the first car on the moon, explored

the Hadley region Apollo-16: the first landing in a highland region of

the moon. Descartes Apollo-17: the last manned flight to the moon, with

the first trained scientist. Taurus-Littrow |

|||||

|

For

only 17-days in the entirety of human history was it possible to look at the

moon and know that people are there.

The

space suit worn by Alan Shepard on the moon’s surface during Apollo-14,

February 1971

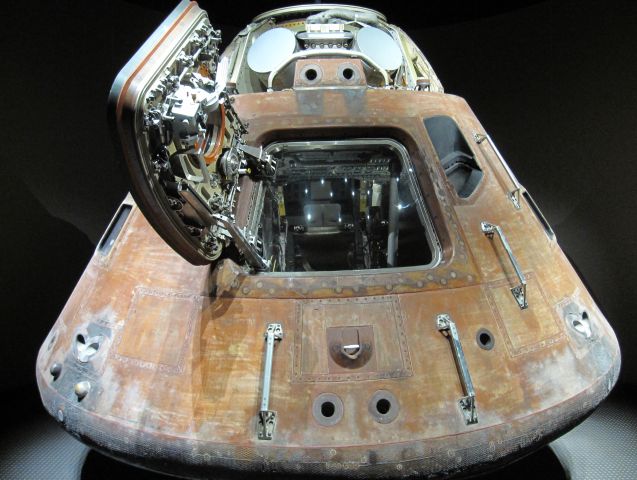

Apollo-14

Command Module Kitty Hawk

Touching

a piece of the Moon. The Human Cost: Considering the risk of early manned

space flight, it is (retrospectively) amazing that NASA did not loose any astronauts during space missions until, that

is, the tragedies that hit the Space Shuttle. However, on 27th January 1967,

during a dress rehearsal for the launch of NASA's first 3- man spacecraft

(Apollo), a fire killed the three astronauts. I clearly recall the breaking

news on UK television, reporting the deaths of Virgil Grissom, Edward White

and Roger Chaffee, on-board an Apollo-Saturn-1B. Their deaths led to a complete

redesign of the materials, electrics and hatch of the Apollo capsule.

The

launch pad (Complex-34) has been left as a memorial to the crew of Apollo-1 It is hard to imagine the effort

involved in achieving John F Kennedy's commitment. There cannot be - there is

not - anything else that mankind has done that can compare with the sheer

audacity of achieving Kennedy's goal, in his words to Congress 25 May 1961: "I believe that this nation should

commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a

man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth." And then on 12 September 1962,

Kennedy enthused: "We choose to go

to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other

things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that

goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills,

because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are

unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others,

too." |

||||||

|

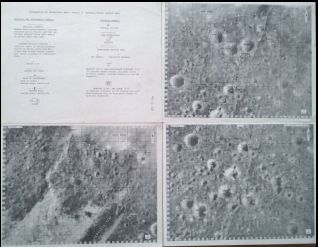

I was sorry to hear of the death of

Patrick Moore. As a young lad I wrote to him on a number of occasions, and he

never failed to reply. I still have the 'official' Apollo-17 lunar

landing-site maps he gave me, which he used on television to describe the

landing location. |

Click

image for a larger photograph |

|||||

|

It is all too easy to look back and

be cynical about those days in the 1960's. But it is never cynicism to

inspire a child. I would not wish to have been born at any other time in

history: not 5-years later, or 10-years earlier. The space race inspired me,

and it shaped me. And for that I thank everyone that was involved in its

execution and broadcast. What

is it that inspires today's children? Suggested

Reading: I have read a great many books on

both the history and engineering of the 'Space Race'. If there is one book I

would strongly recommend, it is "Failure is not an option" by Gene Kranz. If you want to

know what it was like in those heady days, Kranz

has written the definitive description. Kranz was

there from the start, in the thick of it, and his descriptions of those days

are vivid and exciting. The images taken by the astronauts

are, of course, very special. And nowhere are they better displayed than in

the book "Full Moon" by Michael Light. And for the engineers, I can

recommend "The Saturn V F-1 Engine: Powering Apollo into

History" by Anthony Young. This book is, perhaps, a little

too geeky for a general readership: it gives the nuts and bolts description

of the F-1. The Archive of both NASA and The Jet Propulsion Laboratory

are full of great historical information, as well as current projects. Warner Brothers mini-series "From the Earth to the Moon",

presented by Tom Hanks (another self-confessed space geek), presents as close

an emotional equivalent as I think it is possible to achieve, that is if you

weren't there for the real thing. (It

is) Rocket Science: The Saturn-5 was a very powerful

flying machine; in its time far and away the biggest, most powerful, flying

machine ever created – only now, 60-years later, surpassed by NASA’s Space

Launch System (SLS) and Space X Starship. How

powerful was the Saturn-5? The question maybe straightforward

but the answer is far from obvious. There is a ‘mechanical power’ (the useful

power) expressed as that required to lift the weight of the rocket off the

ground. And there is the ‘thermodynamic power’ expressed as that required to

generate the lifting force of the rocket. The Mechanical Power: Any rocket is

only useful if it gets off the ground. You can have allsorts

of fireworks going off underneath the machine, but if the force generated is

not enough to overcome the weight of the rocket it will go nowhere. The heaviest Saturn-5 launch was that

of Apollo-17 - figures taken from the Apollo-17 Press Kit: The total weight of the rocket was

2923461kg The total force imposed by that

weight of rocket is equal to the weight multiplied by the Earth's

gravitational acceleration: Rocket exhaust force must exceed

2923461 times 9.81 = 28679152N The force generated by the five F-1's

was 34096110N, i.e. 5416958N more than the weight-force of the rocket. The

rocket will, therefore, get off the ground. Propellant discharge rate was 13200kg

per second - called Mass-Flow in rocket speak - over 13-tonnes per second: an

astonishing figure! Power in Watts is equal to the force

squared divided by two times the mass-flow: Watts = 34096110 times 34096110

divided by 2 times 13200 = 44035784739-Watts, or 44-gigawatts. Therefore the mechanical power

generated immediately at lift-off is 44-gigawatts. The Thermodynamic Power (the harder

bit to explain): How do you arrange for ejecting 13.2-tonnes per second of

gas from the underside of the Saturn-5 first stage? The answer is combustion: take

kerosene and oxygen and burn them in a combustion chamber to create a lot of

high temperature high pressure gas. The kerosene, with and energy density of

45MJ per kg, is burnt with oxygen at a rate of 3965kg per second kerosene to

9235kg per second oxygen to produce 13200kg of very hot carbon dioxide and

steam: 3965kg times 45MJ = 178GJ per second

– in other words 178GW. A large power station is typically

6GW. At the moment of lift-off the five F1s are producing the power of nearly

thirty large power stations. And all that power is produced in a (relatively)

small space! The combustion products are contained

in a combustion chamber with an exit port just large enough to pass

13.2-tonnes of gas per second whilst maintaining a chamber pressure of around

730000kg per square-metre; around 70-atmosphere. This gas, 13.2-tonnes per

second, is hot, around 3300degC, and fast, nearly 2.6km per second when it

exits the F1 bell. 3300degC is easily high enough to

melt steel; why doesn’t the F1 melt into a boiling puddle? The answer is to

wrap the fuel delivery pipework around the combustion chamber and thereby

heat is removed by vaporising kerosene. Anyone remember, or used, a primus

stove? It worked similarly: the fuel pipe (carrying liquid fuel; alcohol,

petrol, etc.) passes through the flame, the fuel vaporises inside the pipe

and is then delivered as a gas to the burner. The purpose of a rocket bell is to

extract as much force from the high pressure gas exiting the combustion

chamber as possible. Especially during the first moments of lift-off, you

want to exploit all of the kinetic energy to create vertical lifting force.

It is the job of the rocket engine bell to extract all of the force and

direct it vertically. The hot gas emanating from the F1 bell is very hot and

very fast but it is now at normal atmospheric pressure, not the 70-atmosphere

in the combustion chamber. It is for this reason that as the Saturn-5 climbs

higher into the atmosphere (ascending to lower atmospheric pressure) the

exhaust plume begins to expand; no longer a contained column of fiery gas –

however, by that time in the launch the big lift has been accomplished. So there you are: it takes combustion

at around 178GW to create a lifting power of 44GW. Whichever way you look at

it, the Saturn-5, with its five F1 engines, was one beast of a machine. Never

likely to be bettered, the F1 is the most powerful single chamber rocket

engine ever built and used. The best YouTube video I've been able

to find that gives some 'feel' for the raw awesome power of a Saturn-5 launch

is linked below. No music, this time, just the sound of five F1 engines at

full throttle! |

||||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

||||||